There was one novel that grabbed me so hard this year, it put all other books in the shade for months. You must know that phenomenon: a book so delicious, everything that comes after it tastes bland.

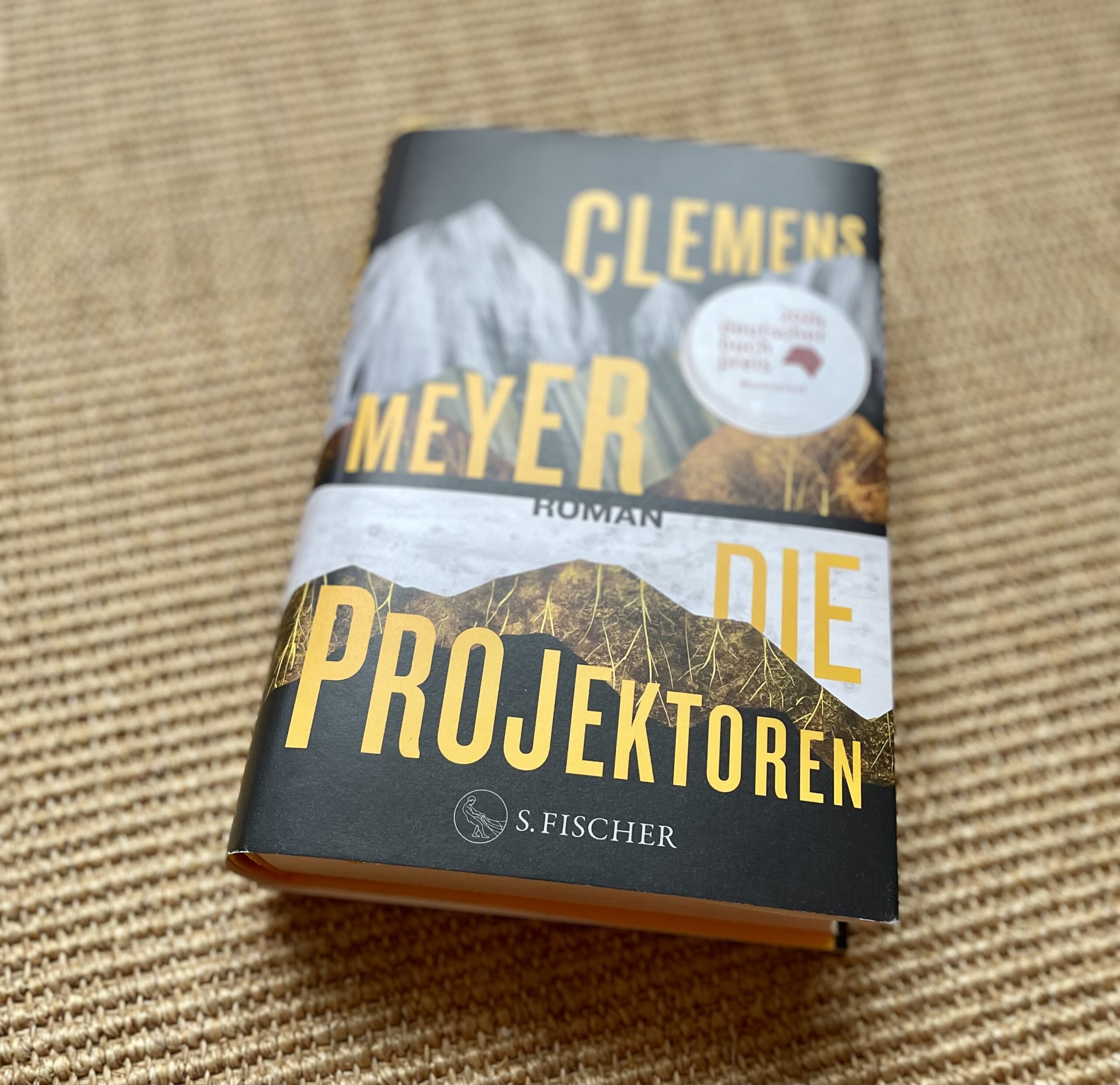

Enough metaphors. It was Clemens Meyer’s Die Projektoren.

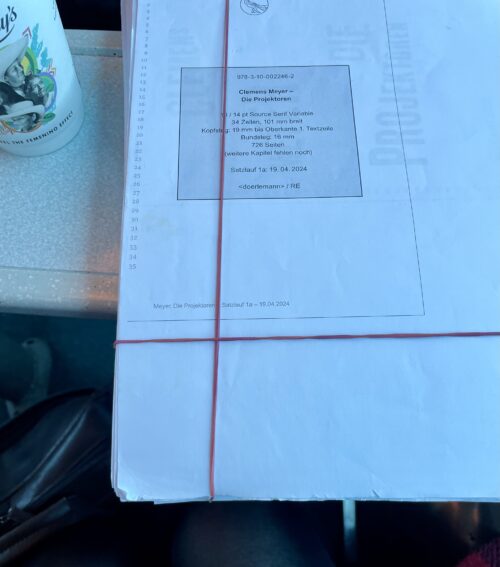

As you may know, I’ve translated most of the author’s previous books. He and I were reading together in Ireland in the spring, and I got a peek at the manuscript on the Cork-to-Dublin train. It’s an unnerving feeling, reading a manuscript right opposite its writer. But I could tell the novel would be enormous, impressive, ambitious – and a little bit crazy. It also turned out to be 1057 pages long, once they typeset it.

A sweeping exploration of masculinity, movies and war, it is set in Leipzig, Hungarian-occupied Novi Sad, Tito-era Yugoslavia, post-communist Croatia and Serbia, and the Kurdish regions, spanning from 1942 to the mid-2010s. Meyer weaves a complex web of characters, times and places, strangely centred around the German pulp novelist Karl May – though he never makes a personal appearance. The book combines tragedy and absurd comedy while warning us of the rise of neo-fascists across Europe. I took a week off from translating to read the whole thing back home, where I found myself laughing a lot, and crying at several points – without ever feeling manipulated.

There are plenty of did-you-know moments. Did you know that the definitive Tarzan actor Johnny Weissmuller was born in Romania? Did you know that both West and East Germany filmed Westerns in Yugoslavia? Did you know that the occupying Hungarian forces massacred three to four thousand people in and around Novi Sad in January 1942? Or that the American Indian Movement (AIM) occupied Wounded Knee for 71 days in 1973?

Meyer creates meaty characters and builds his chapters around them, each in a different style. The projectionists of the title are a shadowy group of psychiatrists, some of them Nazis, who cut across time and place. There’s a romantic hero, a Croatian nicknamed the Cowboy who works on films in the Yugoslavian mountains and goes unexpected places. Marshall Tito and the actors Lex Barker, Pierre Brice and Mavid Popović do all sorts of things they probably didn’t do in real life – while one or two fictional characters from Karl May novels lead independent lives, believing themselves to be real.

Meyer is insistent the book is not historical fiction, and I think this organized chaos is part of that – plus the fact that he extends the action almost up to the present. He’s doing so much more than constructing a palatable story around historical facts. Actually, at times the story is far from palatable, such as when he writes about atrocities, war or neo-Nazis. Yet it is also a celebration of the life-saving power of cinema – quite literally, in one case. A plot does exist but it’s meandering and hinted at rather than driving the novel. I’m not sure I will ever understand it fully, or whether anyone is supposed to.

You’ll be pleased to hear I get to spend all of 2025 translating the book, for English publication by Fitzcarraldo Editions. If you can’t wait that long, there’s a lengthy recording of me reading part of the Novi Sad chapter for the Catch of the Day podcast. I genuinely believe this is a ground-breaking book, pushing the envelope of what writing can achieve.