Short stories are such a big part of my life right now. I’m just finishing my translation of Judith Hermann’s We’d Have Told Each Other Everything – which isn’t actually a short story collection. What it is, I find hard to categorise, but it is a very beautiful and fascinating book about life and writing and it does draw on a lot of short stories. I was lucky enough to receive a small grant from the German Translation Fund, and that has enabled me to take time for close readings of lots of short stories in English. Some are referred to in the book, like the sublime work of Carson McCullers and John Burnside, and some I chose because I thought they might be helpful or because I had them already: Claire Keegan, Maggie Armstrong, Jan Carson. I’ve also been reading the late Margot Bettauer Dembo’s inspiring translations of Judith Hermann’s previous stories.

Starting in 1998 with what became Summerhouse, Later, her collections became bestsellers. I might compare the Judith Hermann phenomenon in Germany (at that time) to Sally Rooney among English-speaking readers: you just had to read her, and if you didn’t you were taking a deliberate stand – and missing out on something exquisite. (Did I, at the time? No, I was too busy having fun and then having a baby, and my German wasn’t yet good enough to appreciate her writing.) Other than Hermann, though, German short-story writers tend not to make the Spiegel Bestseller list.

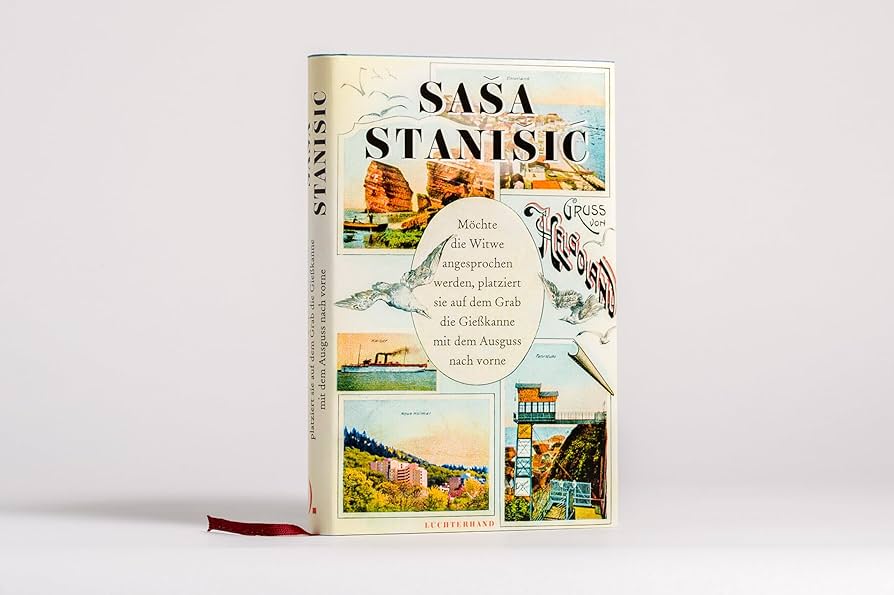

Until now, that is, with Saša Stanisić following up on his German Book Prize-winning novel Where You Come From (as translated with astounding aplomb by Damion Searles) with a sort of short story collection that isn’t. The long title translates as When the Widow Wants Someone to Talk to Her, She Puts the Watering Can on the Grave with the Spout Facing Forward and the book is selling like ice cream on a holiday island.

If you know Stanisić’s work, you’ll know not to expect your classic narrative arc from exposition to resolution – that’s not what he’s interested in. His stories are a long way from the ones I’ve been reading, in other words, but I don’t want to knock either kind.

To me, his appeal lies in his joy in playfulness, from language to structure to the form of his books as a whole and even his approach to the laws of physics. I’d almost call these stories experimental, if that didn’t make them sound dry and unreadable. Because they are delightfully readable, introducing us to all sorts of characters who seem to leap off the page. Many of them get up to slightly strange antics like taking a bath while time stands still, or cheating at games against a small child, or feigning a holiday on the island of Helgoland but finding they committed a heinous crime there despite the lie, or indeed making contact to fellow mourners through the language of watering cans. They’re generally a little hapless, but all the more likeable for it. In short, they are funny.

Although a couple of the stories fit into that mild-mannered category of funny where readers identify with mundane irks in their lives, like the situation comedy of what to put in which recycling bin (I skipped one of these), the others combine an absurd sense of humour with a measure of melancholy. The holiday is feigned, we learn in a later piece, for economic and teenage coolness reasons. Stanisić’s sympathies lie squarely with society’s outsiders: a cleaner, a working-class widow in a gentrified neighbourhood, young single men with not much to do on their small-town Saturdays. Perhaps the occasional first-person narrator is the writer himself; he and his young friends in the opening story are certainly familiar from Where You Come From. And because he wishes his characters well – and because he’s the kind of writer he is – he finds a wonderful and mainly happy solution for them all at the end of the book.

What makes me mainly happy is that the book is doing so well. The last time I tried to read a German bestseller I got bored and angry about 50 pages in, and regretted having made the writer even richer. This time, I was delighted not only for myself, but also for all the other readers who’ll be discovering the joy to be had from unconventional storytelling. Oh, and the language! It’s so rich, the voices are so different – that sparse rhythm of teen-speak or an elderly woman’s interior pep talks, or playful cliché-riding in the Helgoland story. You could buy it and see, and make a daring writer richer.