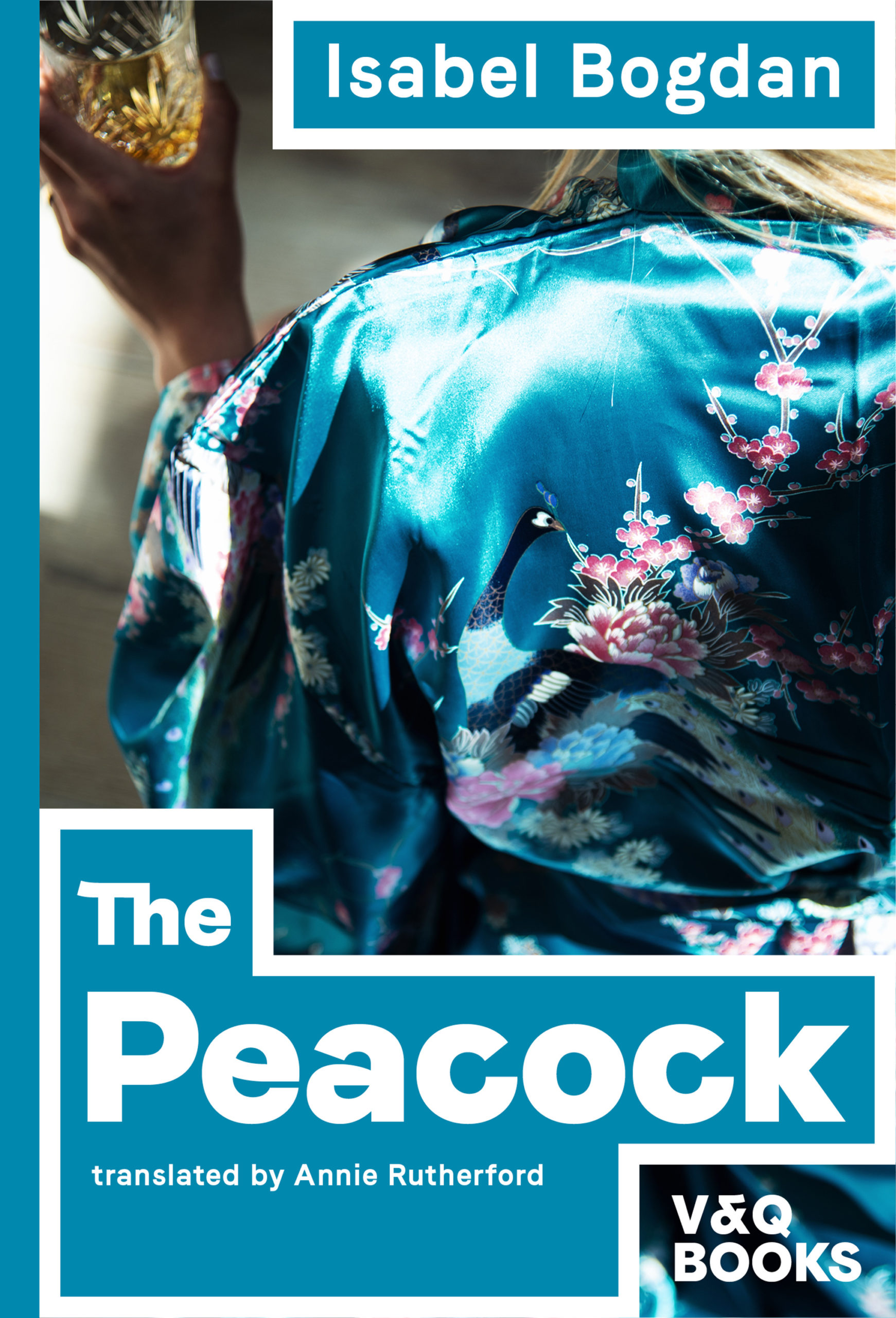

Translator Annie Rutherford tackled the impressive challenge of rendering Isabel Bogdan’s The Peacock – set in the Scottish Highlands but written in German – into English. Here, she talks to Gemma Craig-Sharples about how she went about it.

How did you come to The Peacock?

I was very lucky – V&Q’s publisher Katy Derbyshire actually got in touch with me to ask if I’d be interested in translating the novel. We’d first met at a British Centre for Literary Translation summer school, where I may have, erm, slightly fangirled Katy, and had stayed in touch. A couple of years on, Katy approached me about The Peacock because she wanted a translator who could work with Scots/Scots English. I hadn’t come across the novel before that, but spent a glorious afternoon reading my way through it one sunny day in the park, and I knew this was a book I wanted to translate.

A couple of classic questions here: what were the main challenges you came across while translating? And what was most fun about translating Der Pfau?

In terms of challenges, I was very nervous about getting the Scots and Scots English right in the novel – The Peacock is set quite a bit further north than where I grew up and where I now live, and not only can Scots vary wildly by region, but the Scots language communities are understandably very protective of the minoritised language variants. On top of that, there are real differences in class and background between the different characters (and we’ve got folk from the south of England, as well as from near Loch Lomond), so I was conscious of trying to get those little speech markers right, like sitting room / living room / lounge, for example.

There’s also a lot of talk about food in the book, and that was both mouth-wateringly fun and sometimes quite challenging. I’ve been vegetarian since I was quite young, so I’m pretty clueless when it comes to talking about meat – and there’s a lot about preparing and cooking different kinds of game! I spent a lot of time on google, and also interrogated my various foodie friends. (Big shout out to Megan Somerville here!)

There were so many fantastic things to work on in the book, but most fun was probably translating the humour. I used to work as a tour guide in this area of Scotland, so I had great fun with Isabel’s gentle mocking of the Scottish tourist board. And I think I brought all my frustration with ‘group work’ to the early teambuilding scenes in the novel, and I found a lot of glee in lampooning that.

Though there’s barely any direct speech in the novel – it’s all told through the various characters’ voices and you do such a brilliant job of capturing everyone’s individual style. What was it like finding all these different voices in English? Did you have any tricks or techniques for getting into character(s) while you were translating?

Thanks! I do a lot of talking out loud while I translate, trying to get the feel and the sound of the voice. I spent a good chunk of time wandering around the flat, pulling silly faces and trying to talk like a Scottish laird or a bank manager… (It’s probably a good thing I live alone!) I also used it as an excuse to read and watch a lot of books/films/series set in a similar milieu.

How much of yourself is in The Peacock and in your translations more generally? Is it a case of you taking on the characters’ personas and writing as them or is more a case of you listening for their English voices and writing for them?

Oh, that’s a good question, and I honestly don’t know – probably somewhere in between the two? I’d say ‘taking on the character’s persona’ feels like it fits most with the way that I, you know, wander round the flat muttering to myself. It also depends on the character, of course – I’m probably closest in terms of age and class to Rachel, so a lot more of me went into her than into some of the others.

Other than The Peacock, I’ve generally translated poetry, which of course is a lot less character-based, and although I try to capture the author’s voice, I’m sure that a lot of me goes into them – particularly as I tend to translate poems that resonate with me in some way. I once heard poetry translations described as ‘cover versions’, which I really liked as an idea!

In your translator’s note you talk about Isabel’s Scotland as ‘familiar’. Did this sense of familiarity differ from other texts you’ve translated, and could you say more about how this affected the translating experience?

Yeah, other narrative texts I’ve translated include (extracts from) Arno Camenisch’s The Last Snow, set in the Swiss alps, and Levin Westermann’s remarkable Regarding the Shadows, which is set in a sort of post-apocalyptic landscape. (I do seem to be drawn to mountainous, sparsely populated regions when it comes to translations!) In both of those I first of all had to imagine the landscape, to really try dig into the text and picture what the author was describing – and only then could I find the words for it. In some ways that actually allowed me to be a bit more interpretive. Whereas with Isabel’s text, I know exactly where she was talking about – I’ve been to places like the McIntosh’s castle, I’ve stayed in those holiday cottages, I’ve been on those walks. It perhaps sounds like a blurred distinction, but with Camenisch’s text, for example, I tried to find the closest English/Scots words to those Camenisch used, whereas with The Peacock I was trying to find the best words to describe the places she’s talking about. The thing this probably affected most was the editing process – I was really adamant about some of my translation choices! (One example would be calling the McIntosh’s house a castle, or “the big house”, depending on who’s talking.)

You describe people’s confusion on hearing that you were translating The Peacock from German into English and say that the idea of translating a book written in German but set in Scotland was clearly a ‘novel’ idea. I suppose the ‘bewildered responses’ suggest that people see translation as connected to some experience of ‘otherness’ or ‘unfamiliarity’. What’s your understanding of translation? What does, or can, a translation and a translator do?

Good question. I do think translation can be a window into a different culture, and it can grant us familiarity with people and places we otherwise wouldn’t know. But I think my favourite description of why translation is important, and what it does, comes from the fantastic translator Daniel Hahn: he described a fictional publishing house which only publishes authors whose surnames start with a vowel – and likened this narrow focus to a publisher or reader who’s only interested in books written in English. There are so many amazing books and stories out there – why on earth would you limit your reading by original language?

You’ve spoken before about translations being informed by the time and context in which they’re produced. Do you think the fact you were translating during lockdown changed or influenced your translation or translation process at all?

Hm, it probably allowed me to be a lot more focussed – in a weird way, it was a bit like having an enforced translation residency for a while. But it also meant that I couldn’t do some of the research I’d have wanted to do – I’d been looking forward to lots of eavesdropping in cafes to pick up on ideas for the different voices!

In your translator’s note you talk about translation as a ‘constant dialogue’ rather than a solitary activity, and this idea of dialogue feels really central to your translation approach. First off, you’ve got the dialogue with the author: how involved was Isabel in your translation?

Compared to the poetry I’ve translated, where I’ve really talked through poems line by line with the writers, this was much more hands-off. It was great working with Isabel though – particularly as she’s a translator herself, so she understood all the random specific questions that I had! I think I sent her through my questions once I had a fairly solid draft of the novel, and then later on she of course got to see the manuscript and come back with any points of her own.

And then there’s the crowdsourcing element, which I love. Could you say more about the role this plays in your translations? What are your thoughts more generally on what dialogue and collaboration can bring to translation?

I think translations are always informed by our interactions with other people – so often I’ll be chatting to someone about something completely unrelated and something they say or a word they use will spark an idea for how to solve a translation challenge I’d had running through my head.

I quite often more consciously enlist other people’s help with translation – my friend Ceris loves a good pun, for example, so I often chat to her when I’m struggling with wordplay. Even just the process of spitballing ideas with her may be what sparks the solution I go with. Apart from anything else, chatting to someone can be a lot more conducive to coming up with new ideas than staring at a blank page!

In The Peacock I used crowdsourcing specifically to get try make sure I had the different regional nuances right – I’d ask people what they called an evening meal, for example, and get them to tell me where they were from as well. It was great for building up a map of word usage across regions and generations.

Why should people read The Peacock?

It’s super fun! I feel like a lot of translated fiction can be quite grim or depressing – it’s like we value literary fiction more if it’s very clearly serious. We need more books in translation that can make us laugh – and The Peacock is a great starting point for this.