When you’ve got a winning team, you keep them together… Ivana Sajko’s Love Novel in Mima Simić’s translation was shortlisted for the Dublin Literary Award in 2023, and Every Time We Say Goodbye is just as furious a ride. Working with Mima is a joy – her enthusiasm for Ivana’s work is infectious. And she also writes amazing translator’s notes (read her previous one here).

The original title of this book is Male smrti – Little Deaths. As you’re holding a novel with quite a different name, perhaps we can dwell for a moment on some things that are lost, found or hard-won in the process: the life and deaths of a translation.

Life first.

I have known Ivana Sajko for half my life, at least. I have been translating her texts for many years – performance pieces, a novel. A few years back, our collaboration on her Love Novel got us shortlisted for the Dublin Literary Award and brought us as close as any book can; as a pandemic, as war. (We’ve been through it all). It was a book about love in time of crisis – economic, social, erotic; deeply political, and deeper yet, personal. As I translated it, the world around us collapsed. It was the height of the pandemic, and the book, even though set in a different, past time, encapsulated the present perfectly. Its quiet, and screaming, despair enveloped me in loneliness like a hazmat suit. And it was the nature of my job to re-tailor it for English speakers – for them to breathe in every molecule of desolation as Ivana had breathed it out. I did it; but it took its toll. That short, punchy novel truly knocked me out, and I thought I’d never want to do this again.

Because to translate a book is to live with it, and within it, constantly; to inhabit its images, rhythm, its (a)tonalities, its intricate hurts and grievances, its cultural knots that keep you awake at night, wishing for a sword in place of a dictionary.

Translating Ivana, more than any other author, feels like a matter of life and (little) death – because she writes like her life depends on it. And it does. Much like our life as readers, or translators, depends on writers – the weavers of texts that bind us together, in a (re)negotiated space of some common language and all-too-common human experience. It’s a huge responsibility to help carry this weight. (Or am I taking this job too seriously?).

All in all, it took me more than two years to recover from Love Novel. In the wake of its publication, I declined multiple translation gigs – among them Sara Ahmed’s The Feminist Killjoy Handbook, which at any other time would have served as the most effective defibrillator to my emotional depletion. I truly thought I was done with translating for good – plus, AI would replace us all soon anyway.

Enter death, I guess.

By the time the offer to translate Male smrti came along, I was slowly opening up to the call of the ring, and those hooks that bruised but also made me feel alive. I’d known the book; I had read it when it first came out, just after we’d sent off Love Novel to print. Male smrti was another of Ivana’s famously tight texts, and as a reader, it had sucked me in like a vortex to my very own bottom.

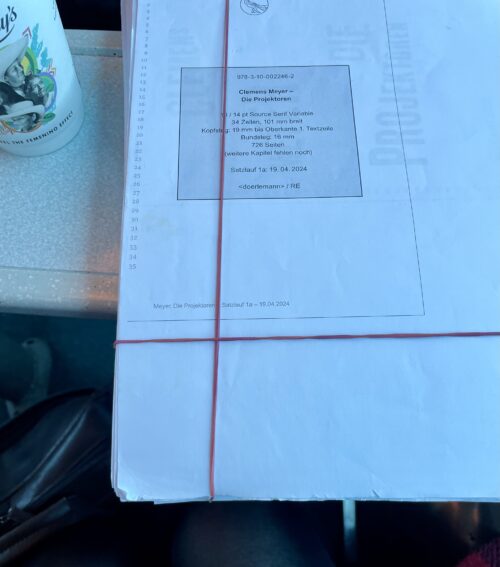

I knew its world, and its journey, well. It was a story about pulling out – no, tearing off your roots; leaving your home (Was it home? What is home?), in some eastern European seaside town, moving to Berlin, trying to plant yourself there, feebly, grasping at the rock-hard ground, withering; constantly turning back and around, in horror, at other people’s little and great, grave deaths – on bleak trains, in migrations and deportations, deaths on vast seas, in tiny vessels.

Ivana’s uprooted antihero, disappointed and disoriented, was me – as much as any text can be any person. This was my life, my dangling roots – rotting or rotten – dragging from an unnamed Croatian town, fraying to dust on my journey to Berlin. Where, ten years in, I’m still finding my way – in the clusters of its neighbourhoods, and in language. Saying no to this book would be saying no to my own life, and deaths.

Every Time We Say Goodbye is a book about eternal movement – the search for oneself in motion, always in relation to an Other. It’s a book about parting, departures, separation, splits – then journeys back, or forth, that aim to reconnect us but often end up just biting our own tails.

I’m not going to sugarcoat it: it’s a tough read. It rams into you with the force of a direct gaze. It doesn’t flinch. It won’t look away, and doesn’t let you, either. Would you want to? Can any of us afford to, anymore?

Each chapter is a single sentence – a series of jabs, a train that runs mercilessly through, across, and over Europe; through its soft tissue, through the hard sell of democracy that keeps failing its constituents to death. Some chapters run for five pages, some twice as much. The thought doesn’t let up.

Our hero is obsessed with his past, with personal and political causes and effects: where does/did the system break down? His obsession urges him to write the world down, pin it into his notebook – perhaps to preserve it, to save it from denial; perhaps to remember it as it once was, and never would be again.

Translating a text can sometimes feel as urgent as that, as meaningful as that. It’s true for this novel, in any case.

Imagine having to take a breath – the longest one. Imagine it seeping in through your teeth and your nose, gliding across your tongue, forking around your tonsils, leaking down your throat. Imagine this slow and steady influx of air, as words, flowing in for ten, fifteen minutes. You’re full? About to burst?

Imagine then having to hold them inside for another ten, fifteen. Until you really can’t take it anymore. Until there’s no oxygen left in you. You’re about to pass out, you’re in that space.

That’s how this book wants to make you feel. And if you’re courageous enough, you will let it. You will let go.

As a reader, you must let go. As a translator, you think ahead. You never lose the rhythm, you don’t lose focus – or you suffocate, you drown. You just don’t let go. Not for a second. You read and reread the sentence-chapter, comb and sift through it like a fevered gold panner. You spot the words and images trickling in from previous chapters; you bring the constellations of words and images back together; you glue and you sew – your stitches sometimes invisible, sometimes in flaming colours, celebrating translators’ sacred service.

The book opens with a journey – and the journey is yours. If it carries you like a wild river, and lands you bruised, in a place unknown, I have done my job well.

Berlin, May 2025