There are two big-budget book prizes in Germany: in autumn the German Book Prize, and in spring the Leipzig Book Fair Prize. The season’s nominees – announced today by the Leipzig Book Fair – get a lot of extra attention, special readings, and a sales boost. They can come from any German-speaking country but Germany does tend to dominate.

Leipzig doesn’t do longlists but it does have three different categories: fiction, non-fiction and translation. The fiction list is the most interesting to me personally, so here’s a bit about the five nominated titles:

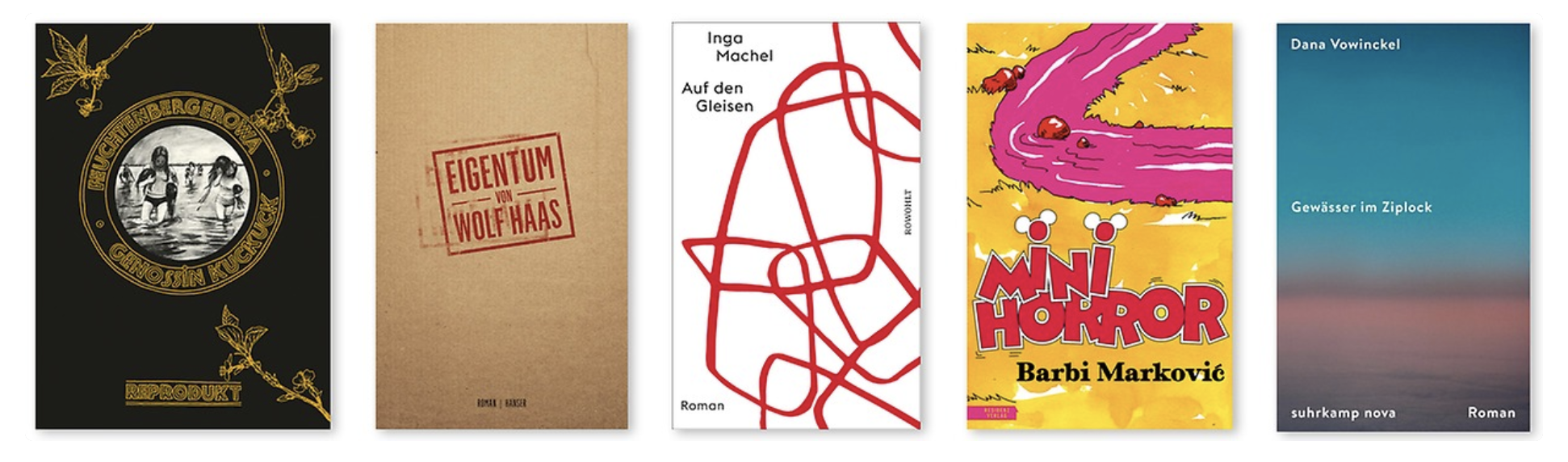

Anke Feuchtenberger: Genossin Kuckuck – the second graphic novel ever nominated (we’re publishing the first, Rude Girl…), it tells a personal story of growing up in an East German village. But it’s also full of fantastic horrors, with girls, animals and fungi apparently “transcending socialist reality”. They say it took Feuchtenberger ten years to write it, and the cover certainly promises a gruesome treat.

Wolf Haas: Eigentum – the Austrian author writes excellent crime fiction, some of it published in English by Melville House, and excellent non-crime fiction. This one’s allegedly an “enjoyable, touching read” in which Haas reflects on his 95-year-old mother’s life and her inability to ever buy property. A good few German-language writers have been tackling poverty and class issues recently, and I like that development. I also like the way Haas plays with language.

Inga Machel: Auf den Gleisen – a debut novel set in Brandenburg and Berlin, with a young man taking a heroin addict for his father, who has recently died by suicide. Through this surrogate relationship, he seems to tackle his grief and his own past. Apparently, it’s written in a fragmentary style in rough language and addresses visibility and invisibility – what’s not to like?

Barbi Marković: Minihorror – the cover makes it look like it has Smurfs in it, which might be deliberate. Belgrade-born Marković tells the story of a couple, Miki and Mini, trying to fit in to big-city middle-class society. Sounds pretty horrific to me, in the best possible way! They say the book’s humour tends towards sarcasm, and they also say it’s a comic in novel form, which I can’t quite make sense of.

Dana Vowinckel: Gewässer im Ziplock – aha, this is the only writer out of the five who I’ve met, at an event in Berlin, but she wasn’t talking about her book so I don’t have a head-start. Another debut, this time set in Berlin, Chicago and Jerusalem with a 15-year-old Jewish protagonist, it’s a tale of a fragmented family and momentous decisions. The judges say it “permits a diversity of worldviews even in the most intimate of circles”, which sounds like it’s more than your usual coming-of-age novel. English rights have sold to HarperVia so you can find out for yourself at some point.

So, a really broad and interesting selection. But I want to add something here about writers and competition. Since Covid, I’ve noticed a lot of Berlin writers being beautifully supportive of each other. It’s most visible on Instagram, where you can tap into a veritable love-fest of mutual appreciation: pub-day congrats, book pics, affection and hearts, hearts, hearts. It’s delightful! I’ve also noticed it at a few recent events: just the other day, with a little gang of fellow writers showing up with balloons and enveloping Laura Lichtblau in hugs at the launch for her novel Sund. And then there was Deniz Utlu and Necati Öziri in conversation about their books Vaters Meer and Vatermal. With two books about Turkish fathers out at the same time (albeit very different novels), the writers could well have been positioned as rivals, but they went absolutely against that and showered each other with praise.

And then Stefanie de Velasco posted on Insta that she’d asked her publishers not to submit her new novel Das Gras auf unserer Seite for the Leipzig prize, because the competition stresses her too much (and because one of the judges has said literature shouldn’t be political, which is obviously bullshit). I instantly thought about my annual ritual of going through the German Book Prize longlist announcement at the outdoor pool with a German writer friend, and how hard it can be for her when she has a book out and isn’t nominated while all those other writers are.

I don’t have an answer. Awards are an effective way of gaining attention for a tiny fraction of the books that come out every year, and watching the benefits to two Voland & Quist authors nominated for the autumn prize over the last few years has been instructive. At the same time, I’m glad some writers are opting out of all the competition and rivalry, which does them no good. It’s not like they’re Blur and Oasis; in fact, they can perform together and collaborate and share and multiply the love. So whoever wins this particular prize, the real winners are… all those loving and supportive writers out there.