In Germany (and the Netherlands, and a number of other countries) the young generation has been raised on a media diet incredibly rich in English-language content. Talk to anyone from about 30 and under, and you’ll probably find they speak extremely good English. It’s amazing! They’re great! They’re on TikTok and all those platforms, and they’re reading in English. Hooray! Good for them. According to the article I linked above, it’s partly because the books they want to read aren’t available in translation, partly because they want “undiluted” originals – and I’d add it’s partly because they want to be part of a global conversation.

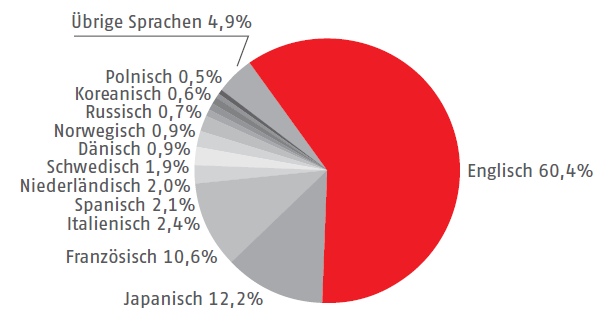

Obviously, there are drawbacks to this for German-language publishers whose cash cows were previously Big American Novels, and especially for literary translators from English to German. But how about we look at this development as an opportunity to change the landscape of translation publishing in Germany (etc.)? In 2022, a whopping 60% of translations published in Germany were out of English. That’s followed by 12% from Japanese, 10% from French, then Italian, Spanish, Dutch, Scandinavian languages, Russian, Korean down to Polish at 0.5%, with “other languages” making up about 5% altogether.

Map that against the statistics of languages spoken in households in Germany. About a quarter of the population has what German statisticians refer to as a history of migration. Probably because that goes back a couple of generations, most of those 83 million people speak only German at home. Then there’s a small proportion (7%) of households who only speak one language in private. We’re looking at Turkish (14%), Russian (12%), Arabic (10%), Polish (7%), English (6% including me, these days) and Romanian (5%). But about 16% of those households communicate in German and at least one other language. That’s lived multilingualism, baby!

OK, I’ll stop with the percentages now, not least because I’m never sure if I can do statistics. Even so, there’s clearly a massive discrepancy between the translations you can buy here and the languages people speak in the country. And that’s an untapped resource if ever I saw one. Heritage languages! Kids who grow up surrounded by Kurdish or Vietnamese but mostly speak German in their daily lives (or maybe English…). These individuals have the exact combination of language skills I think works best for literary translation: really good passive skills in one language, including emotional understanding of the weight of different words and cultural understanding of songs and food and rituals and so on – and often even better active skills in another. The whole existence of heritage languages blows the unhelpful notion of only translating into a “mother tongue” out of the water.

In my utopian future, German publishers will turn increasingly to this group of multilinguals to source translations from languages other than English. Sure, they’ll still pay massive advances to British and Irish and US writers to translate their books into German, but not so many. As literary translators become more visible – names on covers, public appearances, awards, advocacy – more people become aware of our existence. And that will accelerate the broadening of the profession, from the diplomats’ wives of yore, through the “I just fell into it”-generation of people already on the margins of publishing, to a wide cross-section of society. Importantly, since this is a utopian future, translation will pay enough to sustain a decent livelihood: UNESCO will fund literary translations rather than individual countries’ cultural ministries, removing the unfair imbalance in funding availability along with political influence over funding choices.

So we’ll get heritage multilinguals joining the German literary translation community, just as they’re beginning to be more present in editorial roles. They’ll be pitching great titles in languages editors can’t read, or building personal bridges to writers in countries editors haven’t visited. They’ll be tastemakers and trendsetters and they will even out the disparity in what gets translated. Readers and writers will have access to different traditions and innovations, develop greater empathy with characters from different backgrounds to their own, and peace will spread across the globe. I’m looking forward to it enormously.