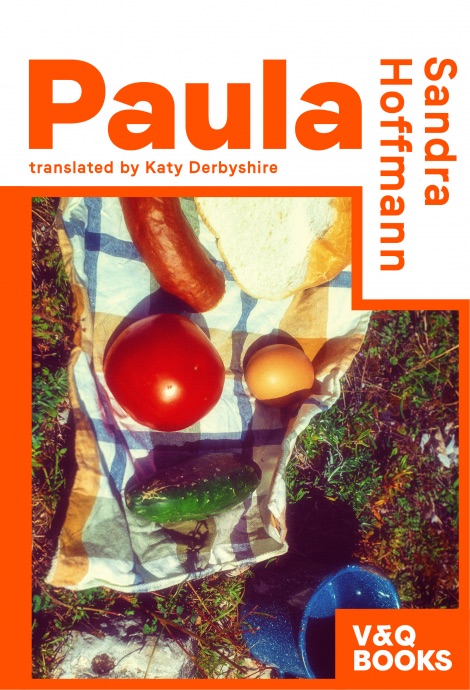

Sandra Hoffman and her translator Katy Derbyshire on their book Paula, on music, the big wide world and the power of speaking.

Katy: In Paula, you write about the time in your teenage years when you started listening to records. A lot of them were in English – Alan Parsons Project, Ralph McTell, Simon & Garfunkel – and I get a sense of a (perhaps typical) yearning for the big wide world from that. What did music and English do to you at the time?

Sandra: All my records were in English, because it really was a kind of music of longing for me. Simon & Garfunkel took me to New York, Ralph McTell to London, and so on. It made me feel melancholy and right, because I always had the feeling this music was making the world a better place. Which it did, somehow. Aside from that, I had a bit of a crush on my English teacher. He was this wonderfully melancholy young guy who sometimes played us English songs in class. He got us to write down the lyrics until we’d got the whole of the song down between us, as a class, and then we’d discuss its content. That was almost revolutionary at the time. No one else was doing that. I wanted to be like that teacher, someone who understands the world’s depths and dark sides, and talks to others about them. All that was in the music as well. Yearning, and wanting a more just world.

Katy: Talking about the world was something that didn’t happen often in your family, did it? Did you have a mental image of a better world, from where you stood then? Have you got one now?

Sandra: No, my family tended to stick to what they knew. There was one exception, though: my father, who worked a lot and was also out and about in the world, spoke very good French, liked good food, took me to the cinema. So he did have a view of the world, and it was him I had a lot of political fights with in my youth. I was a bit of a peace activist: NO PERSHING etc., and my politics were very far left. My father was pro-business, he did want peace but he had no doubts about capitalist ideas. At the time. And yes, of course, I had an image of a better world back then: no more Cold War, no nuclear weapons, no wars.

And seen from today: in a global sense, I think we bear responsibility for this earth we live on, and to save it we have to think more in terms of natural resources and protect them. On the large and the small scale. In our close networks, family, friends, and also on a village level, I still believe in the power of speaking, which connects us rather than dividing us. And when that works on the small scale, it has knock-on effects on the large scale.

Katy: How has that been working for you during the pandemic: speaking? Have you drastically changed your way of communicating?

Sandra: I don’t think so. I’ve tried to stay in contact with the people who are important to me. At least to see them for a walk now and then, have a chat. I make dates to call people or for Zoom coffees. But sometimes I miss the closeness – that we can’t hug or touch, physically, I miss that. And sometimes I worry about whether I can start doing it again once we’re all vaccinated and safe. I really hope so!

Katy: Are you looking forward to travelling now? I assume you started to feel travelling was a normal thing at some point, as an adult, in contrast to that yearning you had as a teenager? How is it for you now?

Sandra: I’m on my first trip right now, since last summer. A work trip, for research. And I’m noticing how strange a lot of things feel. I’m vaccinated but I’m still scared of too many people. I’m so busy dealing with all these impressions: so many people in the restaurant or the hotel. I’m constantly looking around. It’s strange and beautiful now: everything’s new. Almost a child’s view again, because some things have shifted due to the pandemic. But I do love travelling. And I love writing about it. Yes, I do.

Katy: In Paula, you write about an episode in Italy, of all places, where you felt instantly catapulted back to your childhood. But when you wrote about swimming for The Stinging Fly, I got the impression you see yourself as a much freer person now. Can we escape our childhoods, our families – in your case the family silence?

Sandra: I don’t think we can escape our childhoods. But we can sometimes manage to look at them from a distance. In my case, that took a lot of work. I think it’s always hard work. In the end I managed it – after years of therapy – when I spent another four years on the couch of a fantastic psychoanalyst, for four hours a week. I feel like that’s where I became ME. That’s where I worked to permit myself to be the way I want to be, to do what I want to do. To free myself, in that respect, from what had me trapped, by allowing myself to lead a different life to the example my family set for me. I DON’T come from a university-educated family. Even as a teenager, I wanted to be an artist, then again as a young woman, and no one in my family thought that was a good thing. Now I’m a writer. I’ve allowed myself to change the way I live and the circles I move in, which – I feel – some people in my family don’t quite approve of.

Recently, I talked to my mother and my brother on the phone for the first time in ages, and I noticed myself immediately finding excuses for how well I’m doing. Adding in little hurdles, little problems I have to deal with, so the two of them don’t think I’ve got it too good. But I notice what I’m doing right away. Thank goodness.

As to that family silence – there are patterns in a family: I’ve left that pattern. So now I’m outside it. And I’m absolutely certain: speaking helps. Speaking about everything.

Berlin & Munich, June 2021