Katy Derbyshire talks to Karosh Taha about her writing, the novel In the Belly of the Queen, and hopes for the future.

Katy: Hello Karosh – where are you answering these questions right now?

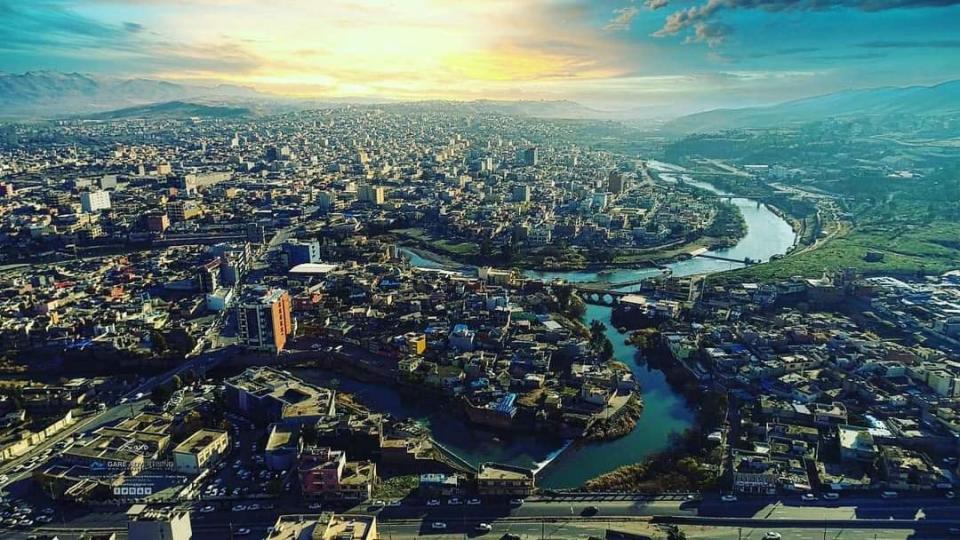

Karosh: I’m in Zaxo, where I’m researching my third novel.

Katy: Do you have a special writing place?

Karosh: I don’t have a particular place where I work; I can write anywhere, at home and in new places. The only place I don’t like writing is on trains – I feel like I’m being watched.

Katy: Let’s go back to the beginning. When did you know you wanted to write?

Karosh: I knew as a teenager – but I didn’t have a strategy for becoming a writer. I didn’t know anyone who could explain the industry to me.

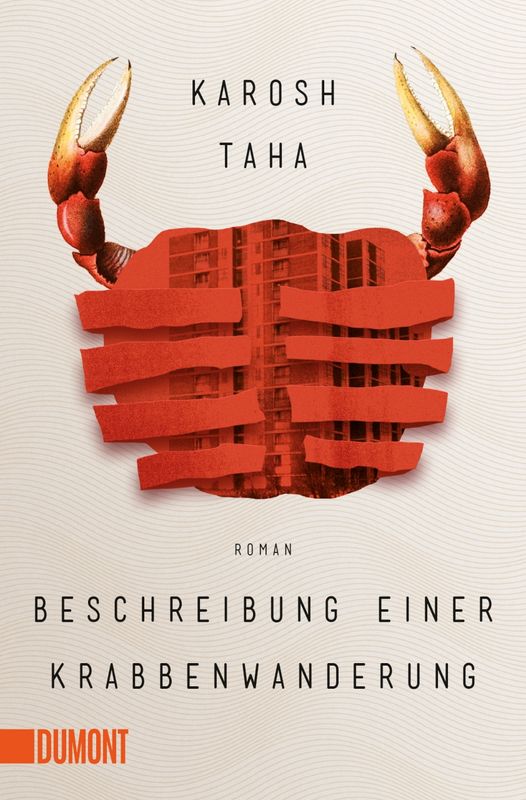

Katy: And what was the journey from there to publishing your first novel, Beschreibung einer Krabbenwanderung?

Many fortunate coincidences. A friend who studied creative writing in Hildesheim (one of two university courses in Germany) told me to contact a literary agency and gave me two different addresses. That was at the end of my teaching degree; I had six months before I started my teacher training placement. So I applied to the agencies. I finished writing Beschreibung einer Krabbenwanderung during my 18-month classroom placement and my agent sent it to publishers. My German publisher DuMont picked it up very quickly.

Katy: Both of your novels so far are set within a Kurdish diaspora in Germany. Was there a particular reason why you wanted to create your Kurdish characters?

Karosh: There was no reason to write about anyone else. I’m Kurdish, I fled to Germany with my family, we lived in a Kurdish community. It would feel like a fantasy if I were to write about Lisa Müller.

Katy: Another thing the books have in common is that they both feature an essay. Is fiction not enough?

Karosh: Both books got very simplistic reviews, riddled with clichés; the white reviewers projected their stereotypes onto my characters and my language. The essays, added to the German paperback editions, are partly there to point out the issues harboured in the books.

Katy: In In the Belly of the Queen, we can choose whose story we read first, Raffiq’s or Amal’s, or we can leave it to chance. I started with Raffiq’s story, by the way, which I know you wrote first, and which I loved for his convincing, straightforward voice with a touch of humour. Was it hard to slip into a teenage boy’s mind?

Karosh: There are a lot of answers to this question. The simplest is: that’s my job as a writer. The more complicated answer is: Raffiq isn’t a real teenager – he’s a construct like all other characters, made up of my ideas of how a teenager thinks and feels, of society’s images of teenagers, but all that falls too short, of course, to write a fully-formed character. A teenager has to be written with the same complex and serious approach as a child, a woman or an old man.K

Katy: What was his perspective lacking that made you invent Amal, and how did you go about writing her very lyrical section?

Karosh: There was no trust between Raffiq and the Shahira character; above all, Shahira wouldn’t tell her story to Raffiq in the way she tells it to Amal. I knew that Amal couldn’t simply be a repetition of Raffiq. The idea at the beginning was for her to be the same Amal as in Raffiq’s story (his girlfriend), but she changed very quickly. After a while, Amal’s character positively imposed itself and I just let her tell her story.

Katy: In your essay for In the Belly of the Queen, you write about missing words for the kind of woman you created as Shahira, a sexually active, self-determined single mother. What I found fascinating was that you list devaluing German nouns like Wanderpokal, Sexbombe – but you also had English terms in the original German essay: femme fatal, man-eater, vamp. I know your English is excellent; how much does the English language influence your thinking and writing?

Karosh: Every language has these misogynistic terms, which was why I included the English words. I read a lot of Anglophone literature, especially US writers, and often in the original English. So it must have some influence on my writing – but I’ve never really thought about how or how much.

Katy: What are your hopes, as a writer, a woman, a Kurdish-German woman writer, a human being?

Karosh: As I said at the beginning, I’m currently in Zaxo in Kurdistan. Today’s the 21st of March, which is Newroz, the beginning of spring – the new year for Kurds and many other people in Western Asia. Newroz is accompanied by a legend of the Kurdish people rising up against the tyranny of an Assyrian king. The blacksmith Kawe took his hammer and killed the tyrant enthroned on a mountaintop. According to the legend, he is said to have lit a fire as a sign of his victory, so that the people knew they had been liberated. It’s a Kurdish myth, but it gives us instructions for resistance to this day.

Katy: Thank you, Karosh!