Translator Mima Simić

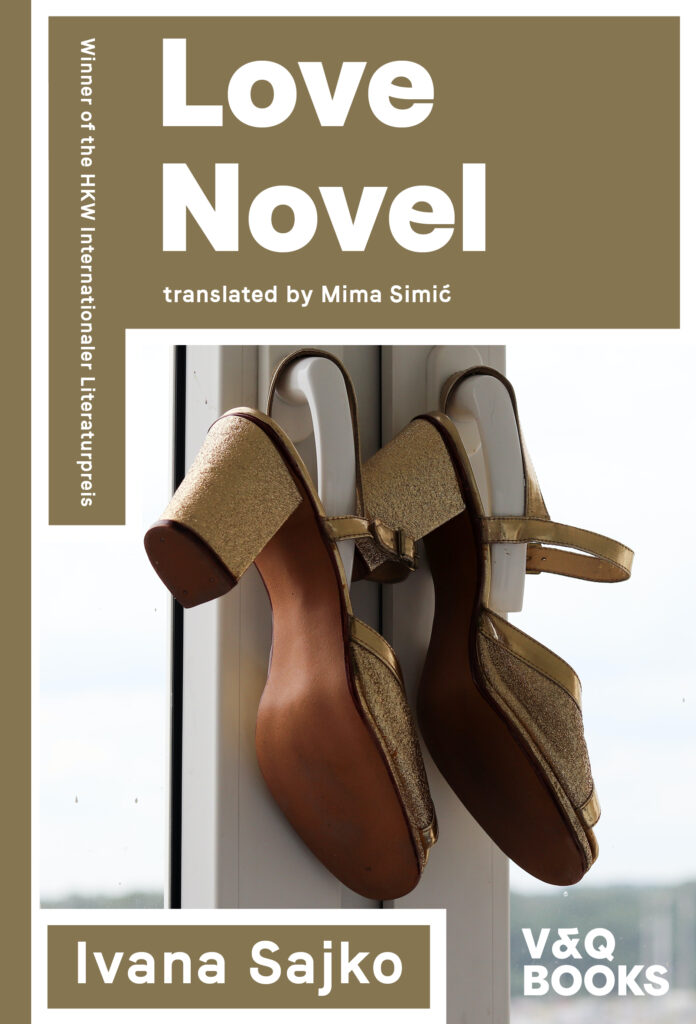

Book cover and author Ivana Sajko

There’s a game I sometimes play in Berlin with my friends, expats from the country formerly known as Yugoslavia; we call it the Poverty Pentathlon. We rummage through our childhoods to come up with the most ridiculous – yet always true! – episodes of growing up in destitution. One of us lived without any heating in the house, warming herself at night with a stove-heated roofing tile. “Yeah, but you had a house to take the tile off!” someone says, and she loses points. Another one had to move every couple of years, from one terrible landlord or lady to the next, intruding into their homes at will, much like swarms of bugs and insects out of the unfinished walls. Here one of us once got bitten by a scorpion, and her mother, a doctor, had to give her a tetanus shot right there, on that bed, a thin two-piece sponge that the whole family of four slept in. The marriage fell apart, there was a lot of shouting and screaming, once there was blood on the mother’s nightgown, right down the middle, in line with her nose. There was no other room to put the kids in, so they watched in silence, swallowing the whimpers of their world ending.

The world of Ivana Sajko’s Love Novel is my world, the world where we are all winners in this wretched competition, clutching our medals as our most precious possession, while they cut into our palms, extending our life lines. Sometimes these lines make for whole books.

Ivana’s world being mine made the work of translation both easier and harder. It is not a long book, but it took me over a year to translate it – I broke many deadlines, too many promises, and finally came through only thanks to the support, eternal patience and grace of our editor Katy (you deserve a shout-out, and a crate of best beer!). But you see, every time I opened the book, it was like a punch in the gut. A punch by someone I knew, a family member.

I would translate a sentence (and Ivana’s sentences, as you have witnessed, are living organisms – each twisting across the page, demanding you harness it, and have it lead you) – and then I would need a break. Sometimes those breaks between sentences lasted for weeks. Going back to the text was like climbing back into the ring with the most intimidating of fighters. (Think Karate Kid meeting Ivan Drago of Rocky IV, if that means anything to you.)

To be sure, a translator needn’t have experienced or lived through any of the events; the political, social/class, or cultural context presented in the book in order to do a good job – in fact, I’m sure that often having all those under your belt can be an obstacle, feeling the text so close to home, wrecked and ruined, so close that you truly believe that no word in a foreign language can absorb the vast world that it is supposed to carry, and birth anew. And this world, you may fear, is just too much, just as it is to live it – it’s too much to take for a language that has no word for tamburica, the instrument embodying the tradition and the deepest darkness of our own version of patriarchal conservatism: How do you translate this sound? Into your language, that does not know pelinkovac, a cheap drink that goes a long way if you want to blackout, yet stay on the “arty” side of the night. (Something like absinth, but not quite). This not-quiteness is something you have to contend with, as a translator, and make peace with, eventually. Befriend, even. Trust that the reader, across the linguistic ocean, doesn’t need to have been slapped to feel the sting of the palm across their face, doesn’t need to have scars to prove that they, too, bleed. After all, their own language, ultimately, is also but a poor stand-in for what, outside of all languages, we all get to experience in the lifelong Olympics of Feelings.

***

Funny, when I first read Love Novel, just as it was published in Croatian – I read it in a single breath, its avalanche of images and emotions carrying me to the final full stop so smoothly that I barely noticed any words. Funny, I say, because once I started actually looking at the words, as a translator, the whole new world opened up; the incredible network of signals, circular references, obsessive thoughts buried in text to be excavated; the incredible force of the rhythm, carefully curated verbs and nouns, and – my favourite of all Ivana’s writerly manoeuvres – her fervent yet seamless switching of tenses, perfectly reflecting patterns of anxious and distressed thought, throwing us back and forth in time, obsessively. It was only when I was given the charge of mediating this book into another language that I was struck by its intricacies, its complexity, and reminded that the art of great writing is to make all the effort invisible. Ivana Sajko has done just that, and I believe – after many rounds in the ring with Love Novel – that this translation has done it justice and we have all come out as winners, clutching at our paper medals, right here on this podium of words.